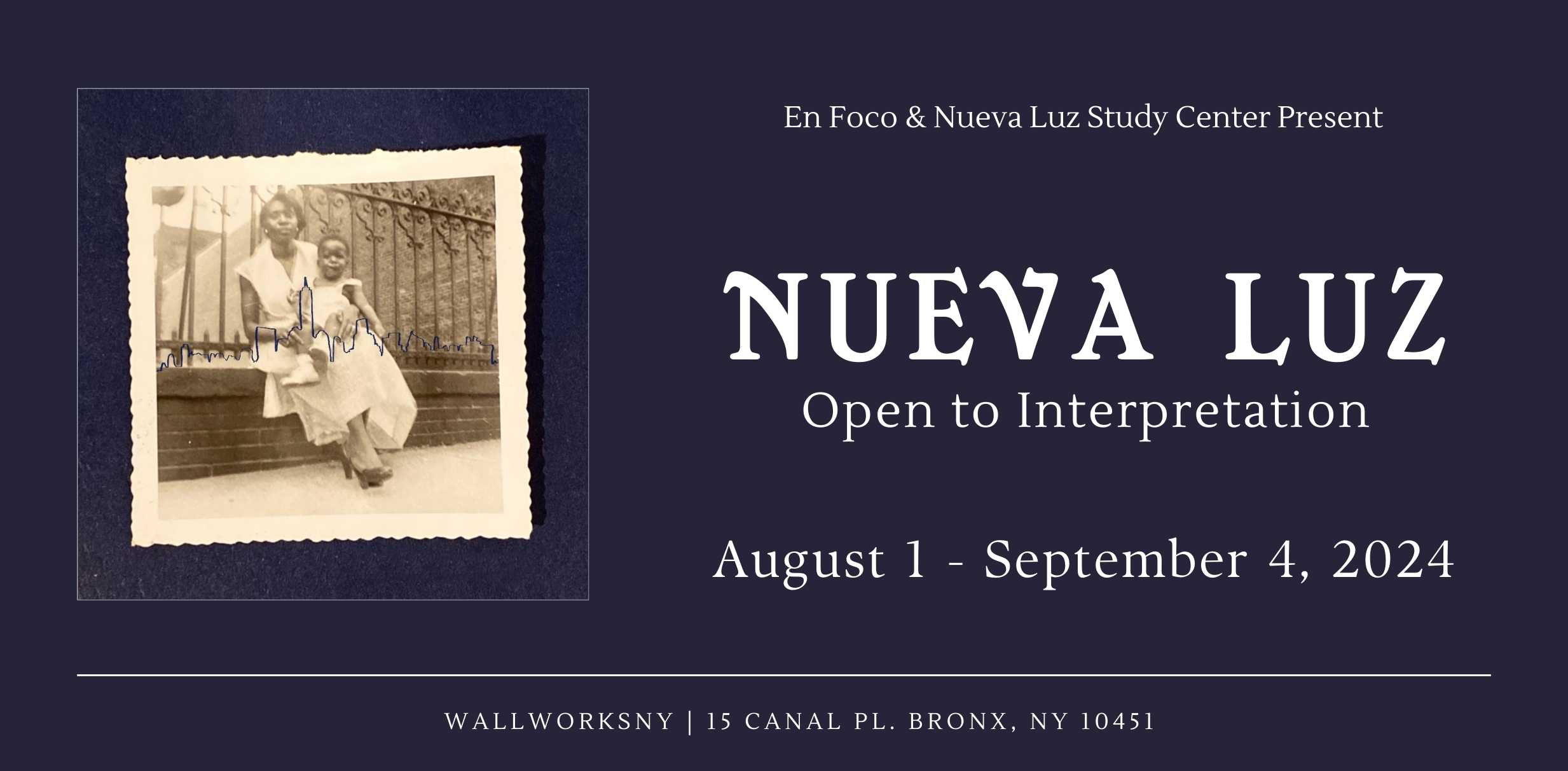

En Foco is thrilled to announce the opening of Nueva Luz: Open To Interpretation, featuring the commissioned work of Shiloah Symone Coley, Lisa Dubois, and Collaborating artists Rejin Leys and Thiago Szmrecsányi. Organized by New York-based curator and arts planner Jennifer McGregor, the exhibition will be on view from August 1 to September 4, 2024, at WallWorks NY, located at 15 Canal Place in The Bronx, New York.

Public Program:

August 31, 2024 – 2-4 pm

Last year, En Foco introduced the Nueva Luz Study Center Commissioning Fund, and embarked on a new initiative to commissioning three artists to create new work and extend their practice using the Nueva Luz as a catalyst to explore historical contexts, artists, and themes from a contemporary point of view. Three projects were identified through an open competition. The selection panel included Felicity Hogan, Director of NYFA Learning at New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA), Michael Palma Mir, from Repertorio Español, and Niama Sandy, multidisciplinary curator, artist, and educator. The artists have been working on their investigations since last fall and will present their projects at WallWorks (August 1 – 28, 2024) and Volume 28, Issue 2 this fall.

In these projects Nueva Luz becomes a window to the past that invites personal investigation in real time. Through research and engagement the artists embarked on journeys prompted by their own practice and interest. Coley invites three contemporary New Yorkers to reflect on the images by photographers in the 1980s which is a springboard for animation. Dubois takes the work of one artist from 2000 to launch her inquiry about how gentrification in Harlem is echoed through her own experience. Leys and Szmrecsányi explore multiple magazine issues to re-imagine the presence of the artists’ spaces in the photos presented since 1985. The artists create an installation that narrates their process and findings.

The Nueva Luz Study Center Commissioning Fund supports artists in extending their practices by accessing the Nueva Luz digital archive as a catalyst for new work on view here. Three projects were identified through an open competition. The multi-part installations were developed over eight months of inquiry.

Shiloah Symone Coley invited three New Yorkers to reflect on images related to daily life by Black women photographers from the first three issues of Nueva Luz in the 1980s. Their observations are the source for this installation, which includes text, storyboards, and animation. Regin Leys and Thiago Szmrecsányi examine the way that artists’ spaces are portrayed in photographs published in Nueva Luz during its first three decades. The resulting installation documents their findings. A series by Adrienne Odom featured in a 2001 issue informs Lisa DuBois’s study of gentrification in Harlem, supported by her own documentation, experience, and contemporary interviews.

The exhibition is an exchange between the images presented in Nueva Luz with current ideas. The magazines the artists drew from are linked below and the exhibition will be documented in the magazine’s fall issue.

I invite participants, collaborators, and viewers to re-write and interrogate existing narratives. What started as a cross-generational collection of audio recordings and visual archives to document a collective familial rememory of intergenerational Black womanhood morphed into an exploration of the complexity of narratives at the personal, familial, and communal level. I take an antidisciplinary collage approach, exploring the narratives present in existing archives while simultaneously creating new, more intimate familial and community archives driven by personal narratives. My most recent projects are experimental animated shorts exploring the interior lives, feelings, and emotions of Black women.

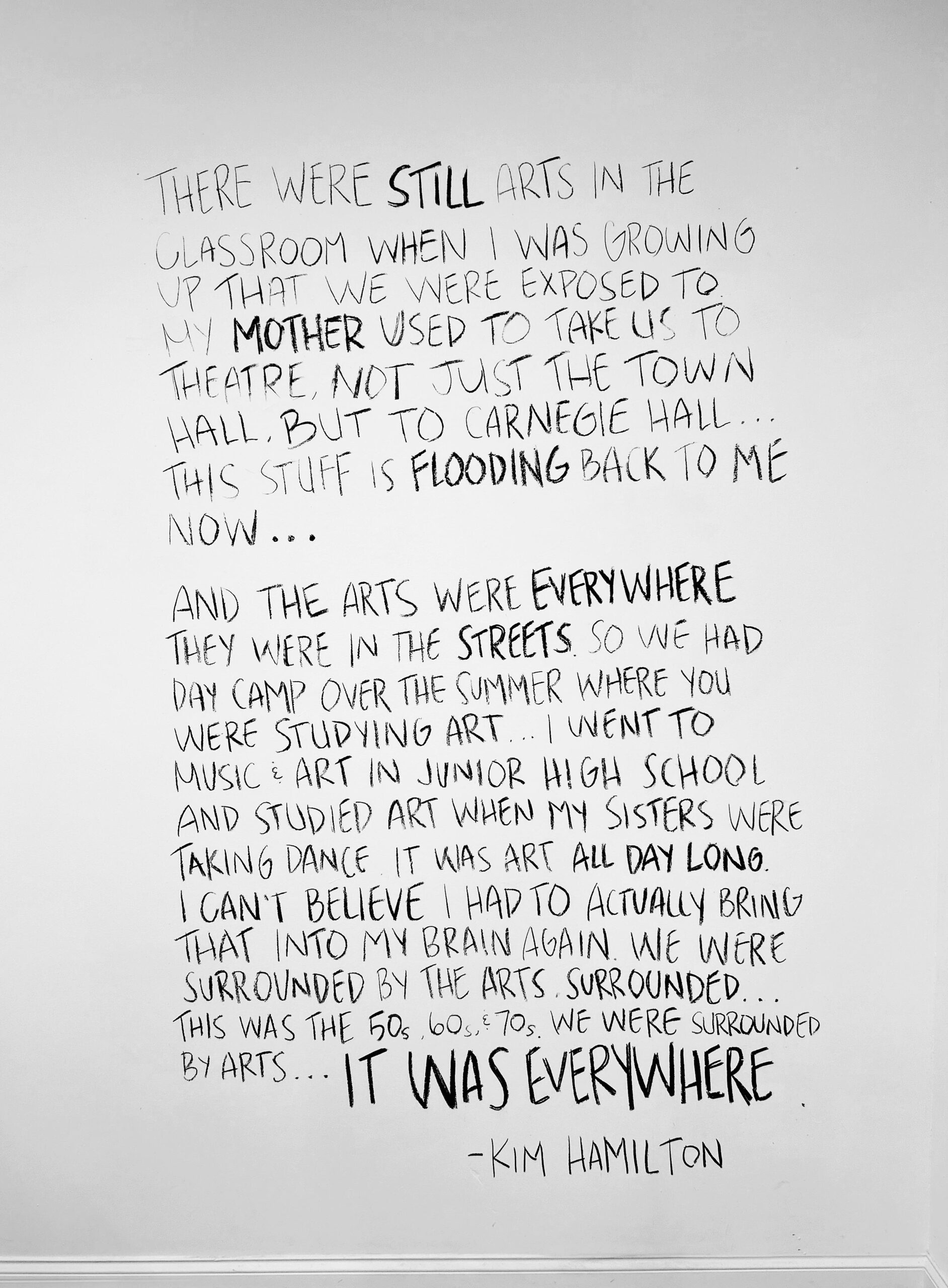

“You see all that blue stuff?” is an installation consisting of three parts: 1) An interview excerpt, 2) A storyboard, and 3) an experimental animation. Three lifelong New Yorkers – Yeline Del Carmen, Kim Hamilton, and Valerie Nero – responded to the works of Black women photographers capturing daily life in the early volumes (1-3) of Nueva Luz – Coreen Simpson, Marilyn Nance, Carrie Mae Weems, and Clarissa T. Sligh. Each part explores a thought, feeling, or experience that connected these women to the work and to each other. The sequence of the work is intentional, displaying not just content, but process.

Shiloah Coley is an artist-scholar and cultural worker dedicated to tending to and cultivating community through storytelling. Her mother taught her to use her voice. Her father taught her to listen. Her grandmother taught her to ask questions. She utilizes storytelling as an avenue for encouraging agency-activation with marginalized youth and elders. She’s designed and facilitated public art projects with The Bubbler at Madison Public Library (Madison, Wisconsin), Play Africa (Johannesburg, South Africa), the Madison Children’s Museum (Madison, Wisconsin), and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, New York). She was a 2021–22 Sherman Fairchild Fellow at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, where she subsequently completed a commissioned project. Previously she conducted research about the implications of digital redlining on cultural preservation in Black communities in Baltimore, Maryland, with the Billie Holiday Center for Liberation Arts at Johns Hopkins University.

The gentrification of Harlem peaked in the early 2000s. Harlem looked like a war zone. I observed the process of erecting new structures and the remarkable destruction of preexisting ones. Using a point-and-shoot camera, I casually captured photographs of what I observed, knowing that these shots would eventually reveal the history behind Harlem’s transformation.

The Fall and Rise of Sugar Hill: An Observation on Gentrification in Harlem

By Lisa DuBois

I grew up in Sugar Hill, a neighborhood of Harlem known for the sweet life, but in the sixties, it had become a memory of the glory days of the Harlem Renaissance when the hill was populated with many affluent Black leaders and actors. When standing at the highest point of the steep hill at Amsterdam Avenue and 145th Street and looking east, one’s line of sight extends for half a mile until reaching the edge of Harlem’s east side.

One of my uncles purchased several buildings in Harlem during the white flight. He owned a six-storey building at 545 West 148th Street where I lived with my family. The door was flanked with four stone lions and elegantly inscribed with the name “Bernice” in faded gold letters, symbolizing a bygone era. The name, with its Greek origins meaning “bringer of victory,” was well-suited for the mindset of original European residents who I am sure felt like victorious pioneers in a new world.

My grandparents, uncle, and aunt lived in their own apartments in the Bernice which gave me a deep sense of security and connection to my family. Dr. Vernon Baker, our physician, was a family friend and had his practice in an office on the first floor. As a child, I played with my friends on the street and the elders sat on the stoops. Three churches on the street have managed to stand the test of time. On Sundays, I recall the captivating gospel singing that resonated from the Baptist churches as we made our way to our Catholic church, where the music was practically nonexistent and lacked excitement and passion.

My father lived a long life and passed away in the building at one hundred years old. My final memories of 148th Street are a protracted two-year lawsuit against the landlord. I lost the case to keep the apartment and received a small recompense relative to the gentrified worth. This ordeal affected my views on gentrification. I avoided going back to 148th Street and would purposely drive around it to avoid confronting the feelings attached to that experience.

When I made the decision to go back, I noticed the original door to my old building had been replaced and is now known as “545.” The four stone lions guarding what had been the Bernice remained, but the eyes had been painted gold—a kitschy trend that began in the early days of gentrification.

I parked beside the Baptist church and let the soft echoes of the music take me back in time, a particular type of bittersweetness that emerges from the memories of a familiar location. To my own surprise, after this trip, I would soon realize that in time my views on gentrification would change when I looked at it from a different perspective.

In the seventies, New York was grappling with one of the worst drug epidemics in its history. Harlem was severely affected and Amsterdam Avenue was saturated with heroin addicts, making it necessary for me to change my route when going to school. During this time, I received a scholarship to attend the Windsor Mountain boarding school in Massachusetts, and I left Harlem for four years.

Upon returning home from school, I observed significant changes. A considerable number of brownstones were condemned and for many years, it seemed like Harlem would remain in a perpetual state of uncertainty and deterioration as many people began to move. hen I learned the term “white flight” it triggered a memory of the last remaining white resident in my building, an elderly woman, Mrs. Reid, who always seemed angry, lonely, and out of place. Now I understand why.

Just as Harlem was detoxing from heroin, crack became the new drug of choice in the eighties. At this time, Harlem began to exhibit a combination of traits that positioned it as an ideal candidate for gentrification. Its geographic location offers proximity to the Hudson River and Riverside Park on the west side and to Harlem Meer lake in Central Park on the southeast side.

When low-income residents reside in desirable locations and the neighborhood begins to decline, gentrification becomes an appealing incentive for real estate developers. Deals are executed between landlords and brokers, which has been customary throughout history.

In the early 2000s, Harlem experienced an accelerated period of renovation and construction. I captured photographs of some of these changes knowing that this urban landscape would soon undergo a significant transformation. The strange sculpted faces and animals in the buildings’ façades that seemed to glare at me reflected the culture of early residents of Harlem.

In 1684, when Dutch settlers moved north to Manhattan, they were accompanied by enslaved people and indentured servants. The area was undeveloped wilderness and they soon found themselves in conflict with the original inhabitants of the area, the Wecquaesgeek people. The unbalanced power distribution led each person to develop their own crude methods for survival in the newly conquered land.

There is a strong argument to be made that the systematic ruthless removal of Natives was the first form of gentrification in Manhattan, since the process involves the displacement of one community that is replaced by another, typically composed of wealthier individuals who possess greater power and financial resources to invest. The community unravels and fights to survive as it experiences the legal but insensitive process of gentrification.

When gentrification takes hold, it permanently alters the neighborhood in a way that can never be restored. When I went back this year to photograph the same buildings from 2004, I realized that there were whole new sets of buildings that were being renovated and that gentrification is a continuous cycle that never ends. I began to adjust my own philosophy with the indisputable reality that change is unavoidable and necessary. By applying this concept to gentrification, I began to perceive it differently.

I am uplifted and encouraged by knowing that during the early stages of gentrification, there was an unseen force at work. Harlem visionaries who understood the seriousness of the situation worked hard to preserve the history of Harlem. Statues of African American heroes were erected and new street names were added to reflect the all-African American community that existed in the pre-gentrification era. There are many aspects of Harlem culture that draw scores of tourists each year which is one of the reasons why it is crucial for a vibrant Black population to thrive in Harlem.

Predicting Harlem’s future is challenging, but it is highly likely that such institutions as the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture will endure and continue this work. I realized that gentrification was a multifaceted phenomenon that can provide both enormous benefits and devastating drawbacks for different groups of people. Gentrification does not end; instead, it evolves.

Lisa DuBois, a visual artist and curator born and based in Harlem, showcases her diverse talents across various genres, including traditional photography and digital surrealism. Her work has been exhibited nationally and in India, France, and Greece. She has worked as a curator and creative consultant for Art on the Ave (New York, New York), Social Documentary Network (Concord, Massachusetts), En Foco, and Pro Arts Jersey City (Jersey City, New Jersey). She established Harlem’s X Gallery, a collaborative venue and online platform for local artists and photographers. Publications such as The Guardian and The New York Times have recognized her artistic and curatorial work. At Social Documentary Network, she serves as both the photo editor and diversity advisor.

In Live, spaces like a family home evoke ideas of origins, displacement, fears, and dreams. They bridge time and space, and family ties, among other meanings. Throughout Work, places reveal social roles, routines, gender and cultural identities, or disclose self-transformation. We also get an insight into the photographers’ practices. Inhabit points to how we live in the world today amidst inequality, racism, exploitation, war, environmental disasters, and dispossession, showing us who’s in control and in the margins.

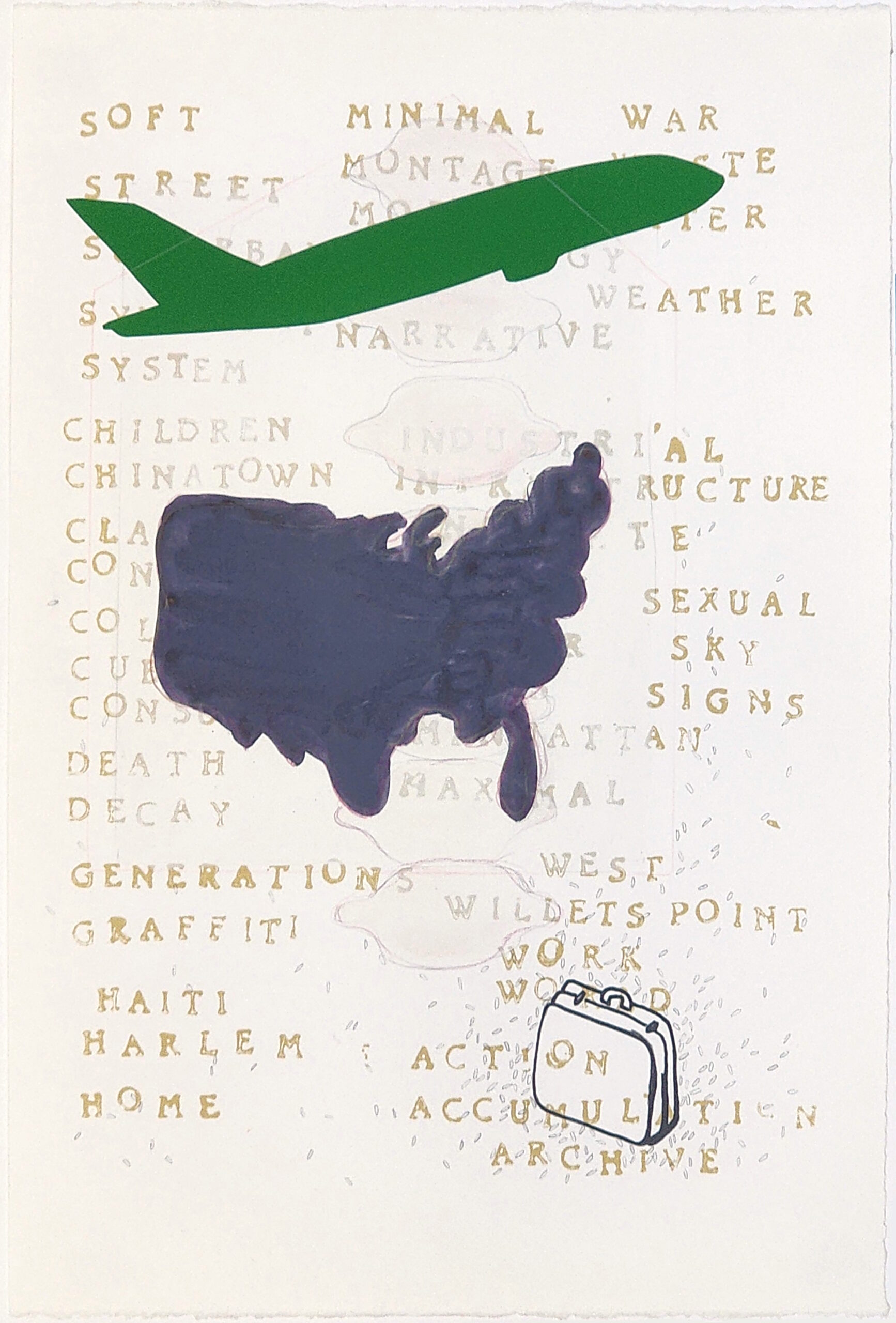

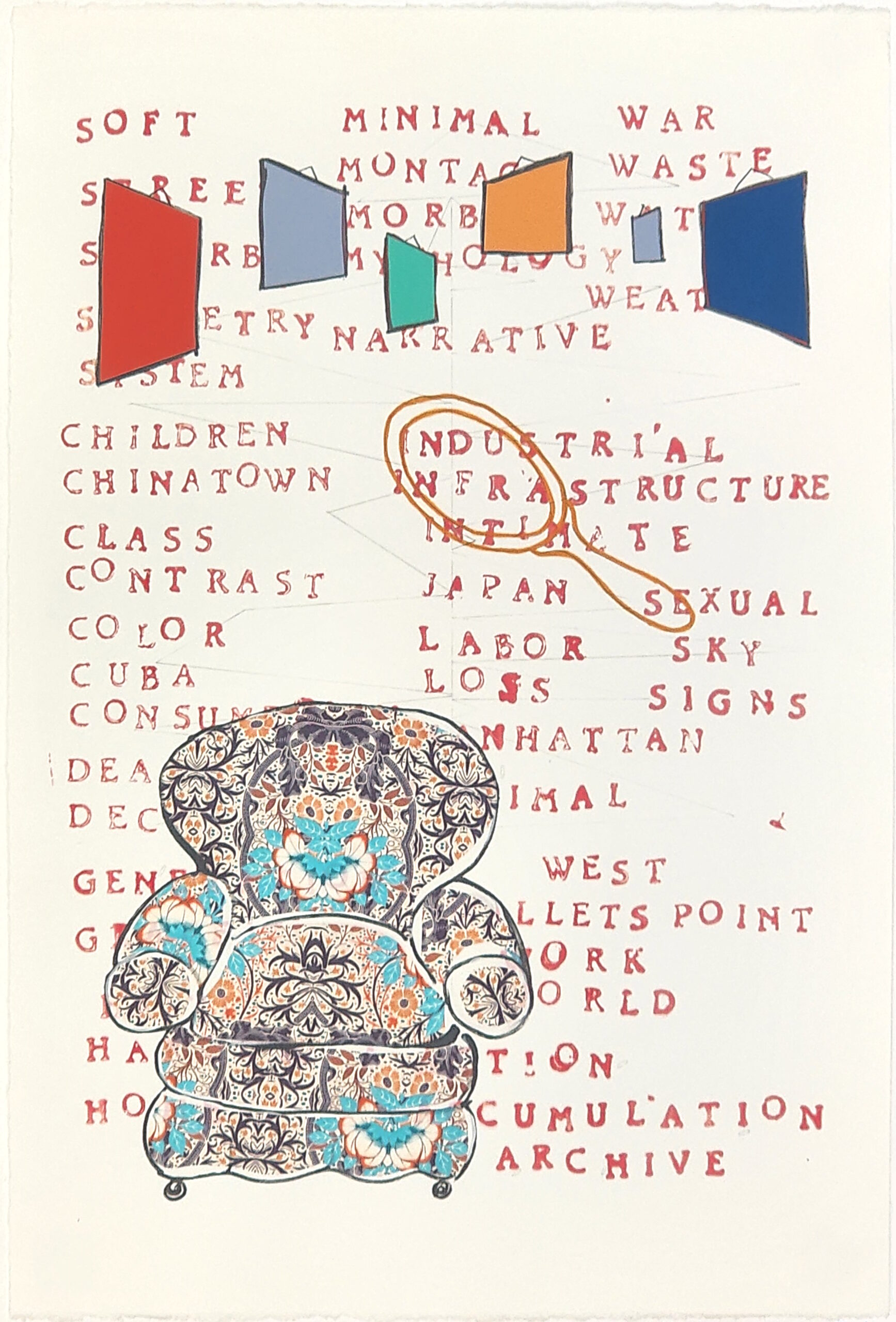

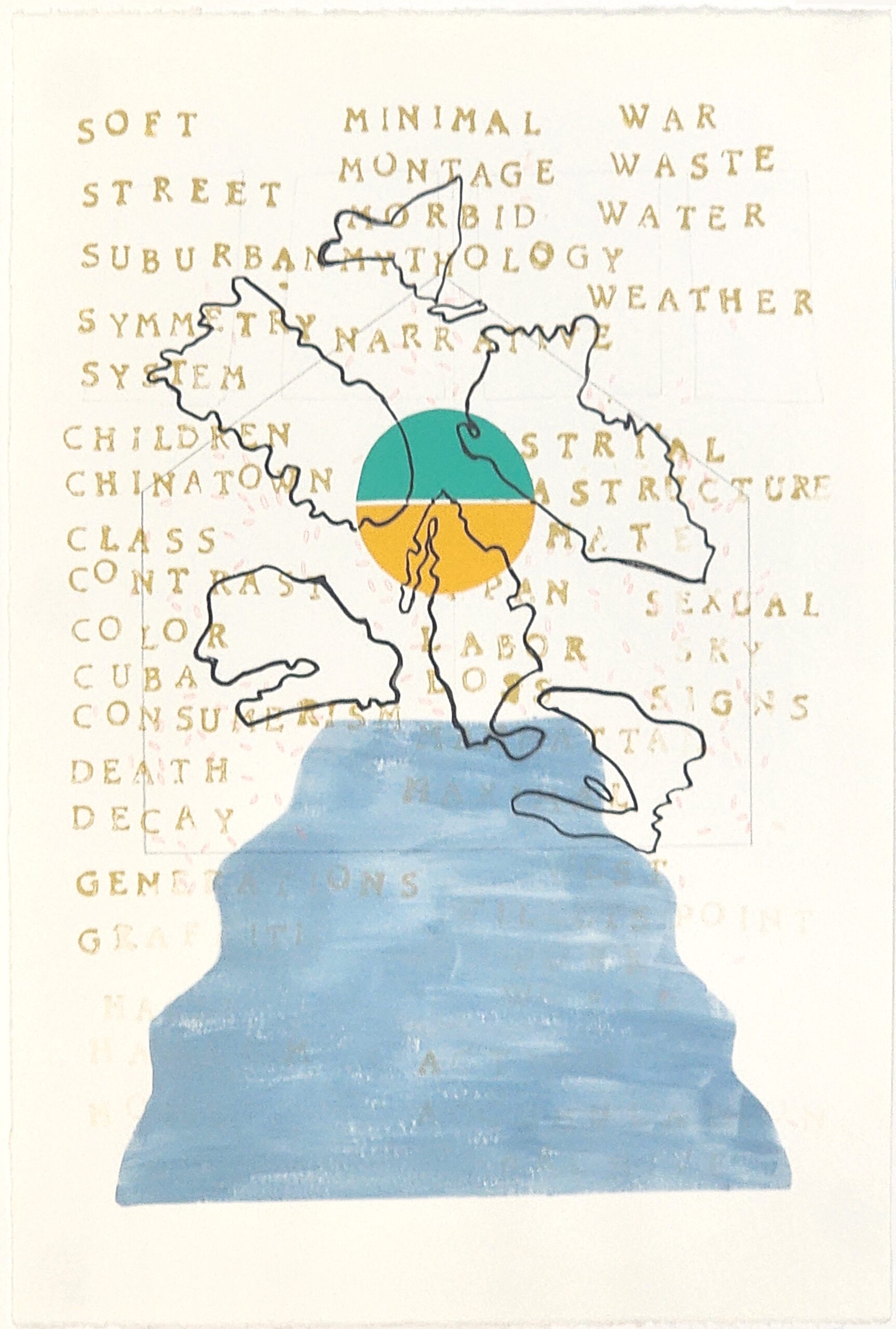

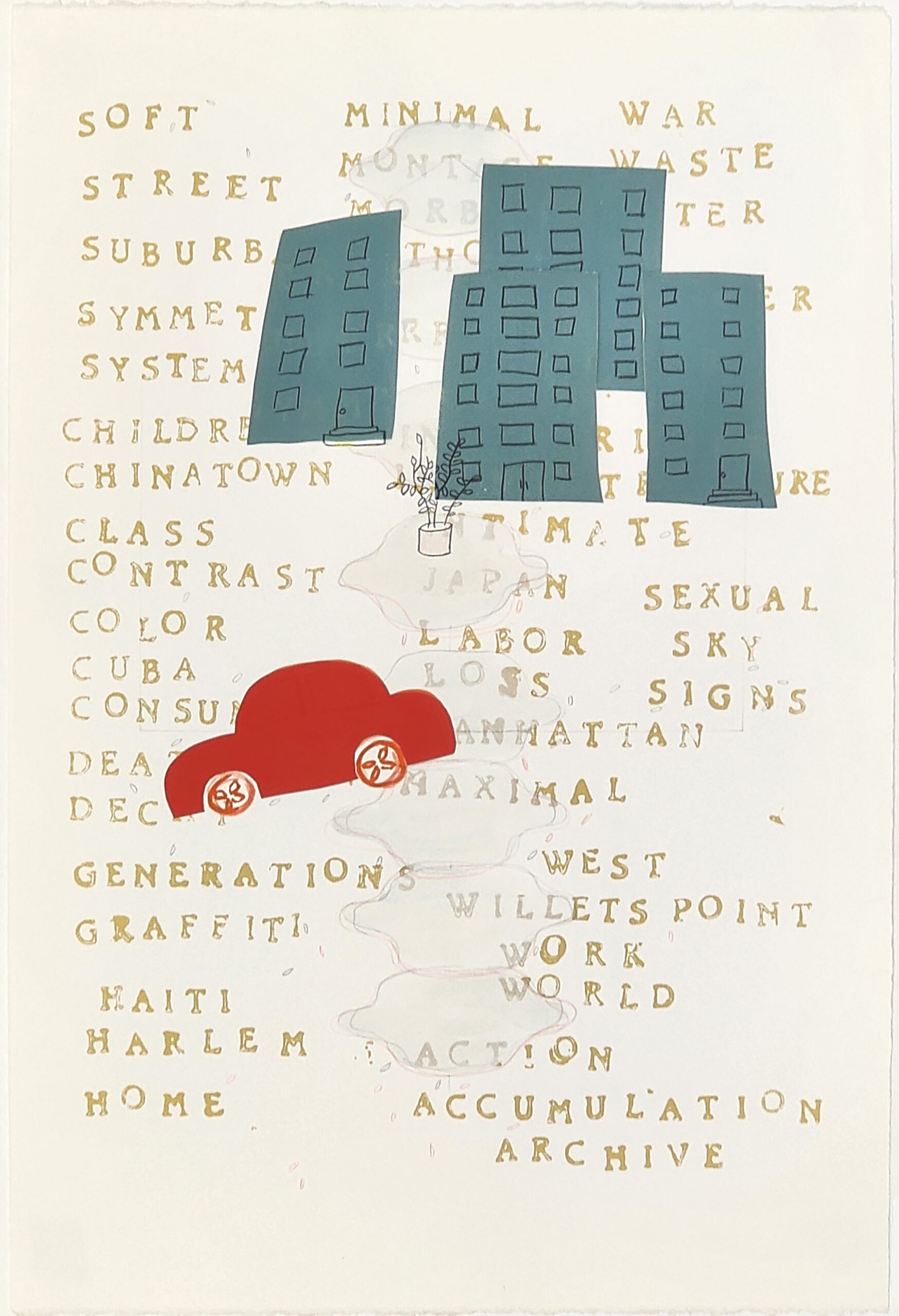

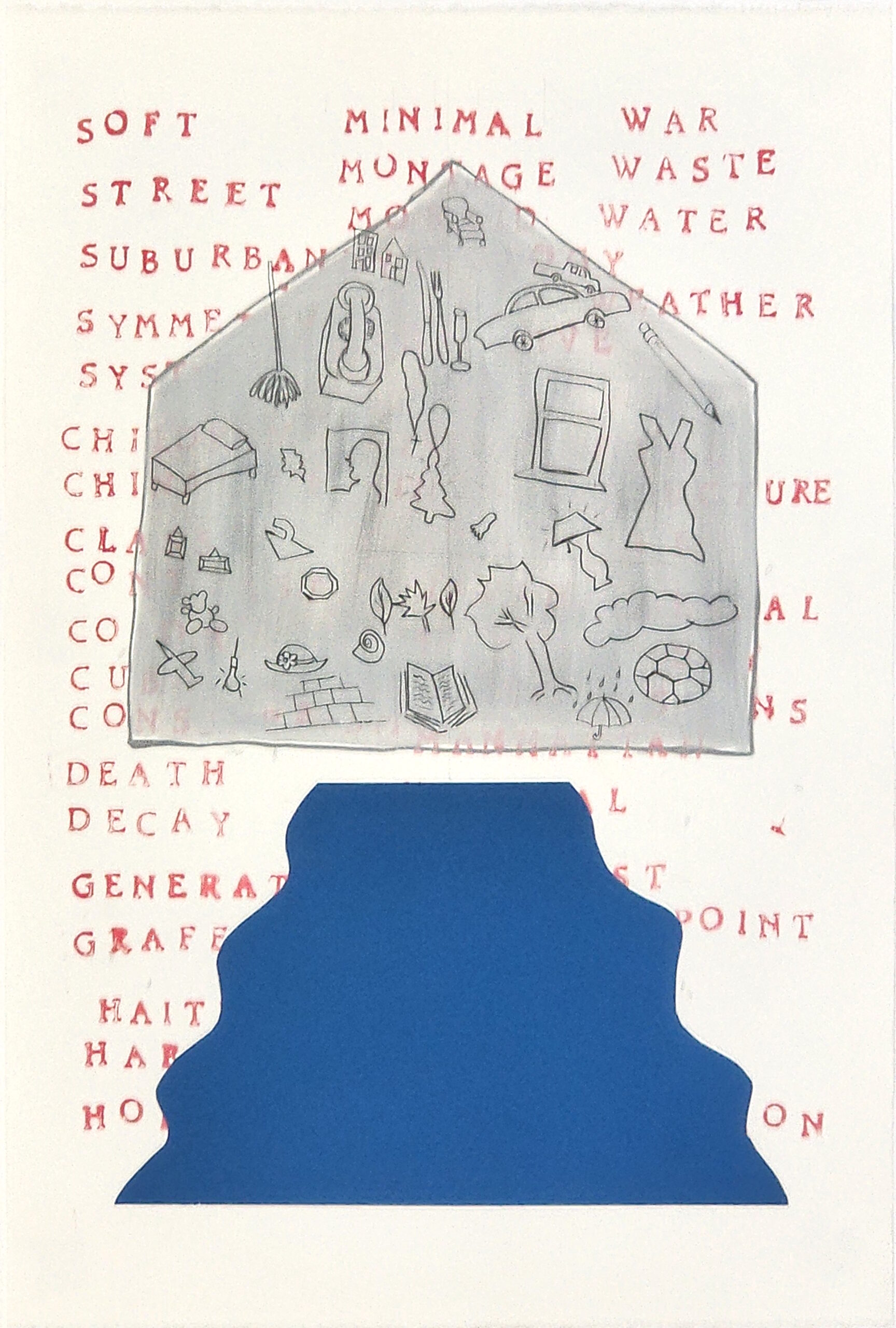

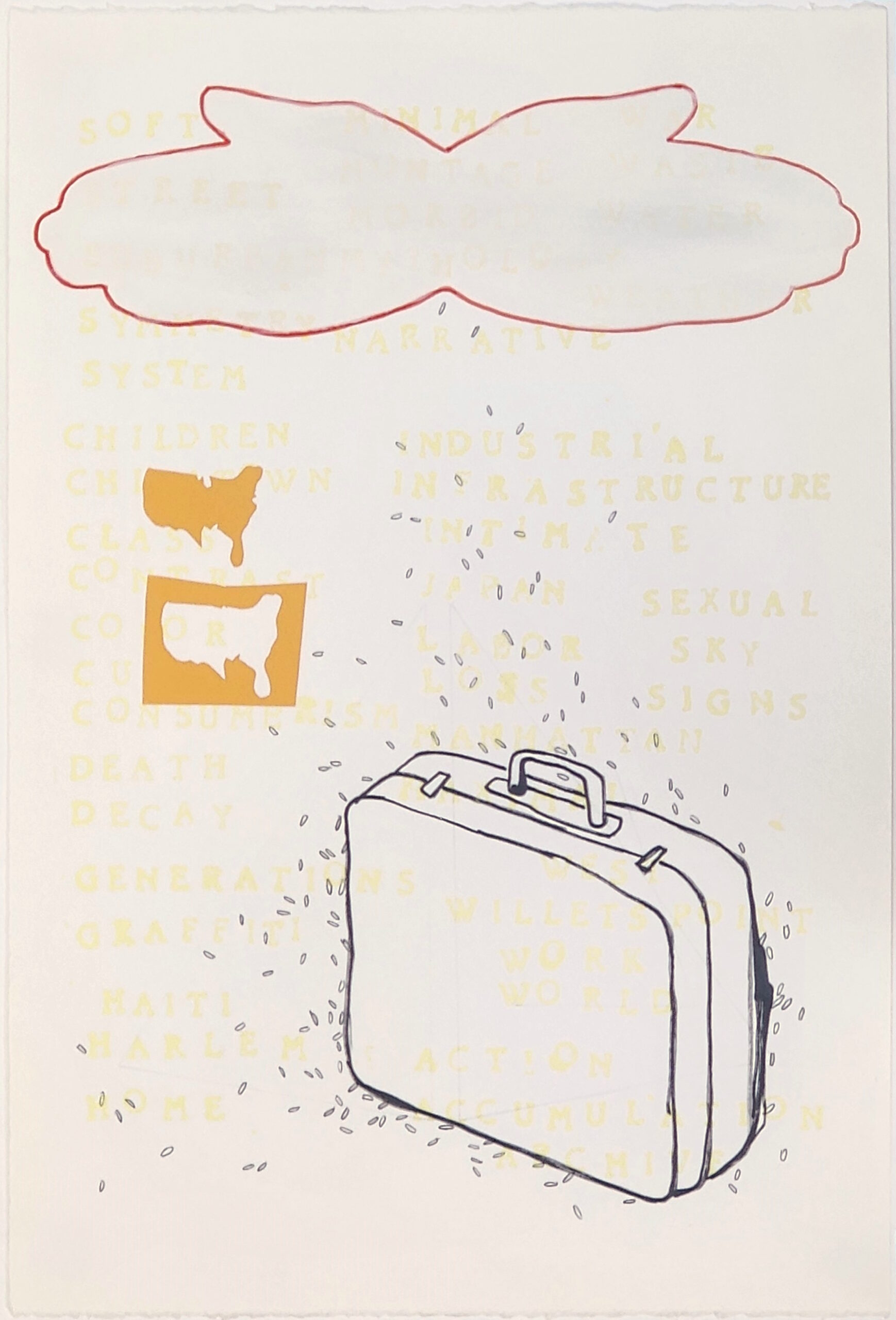

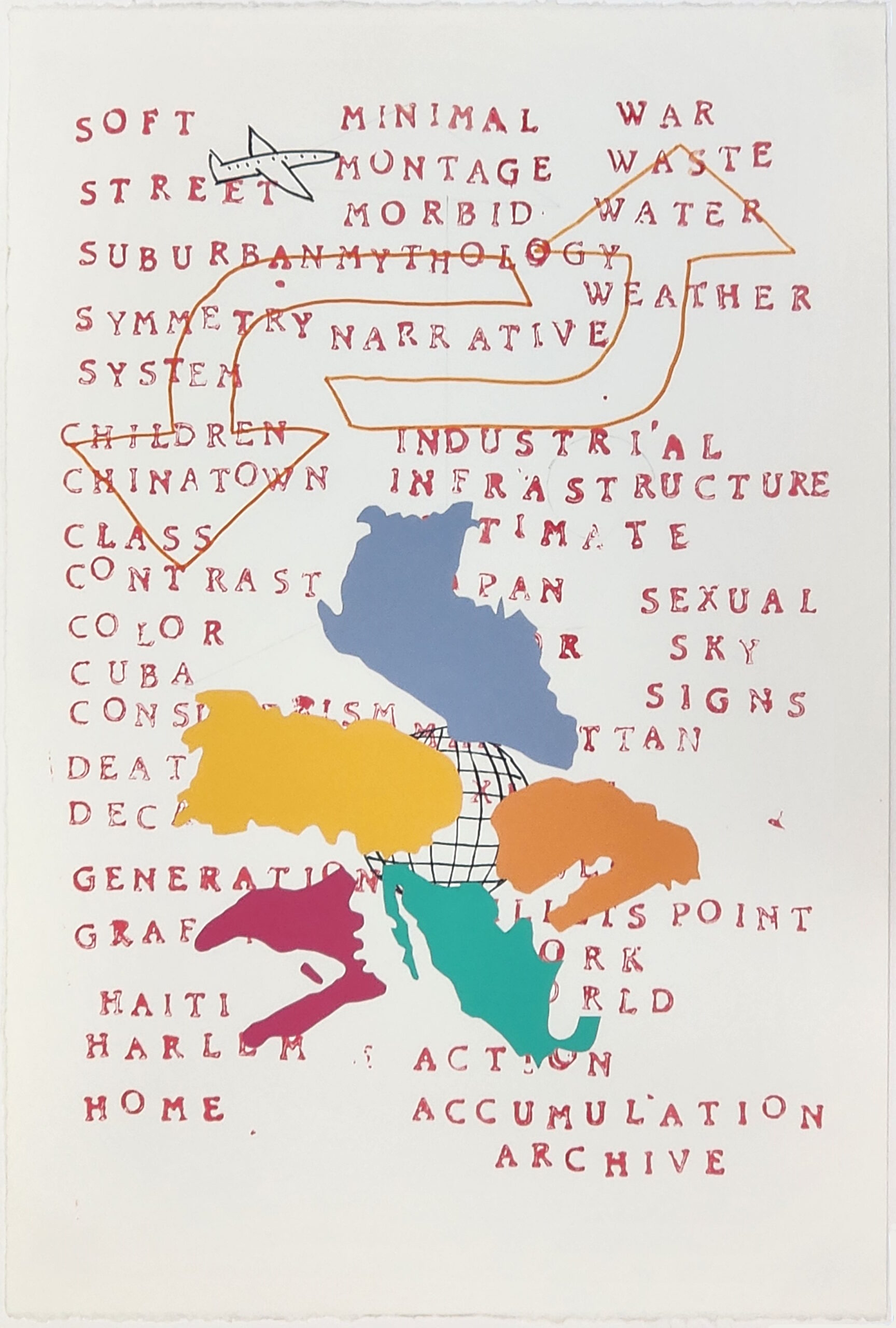

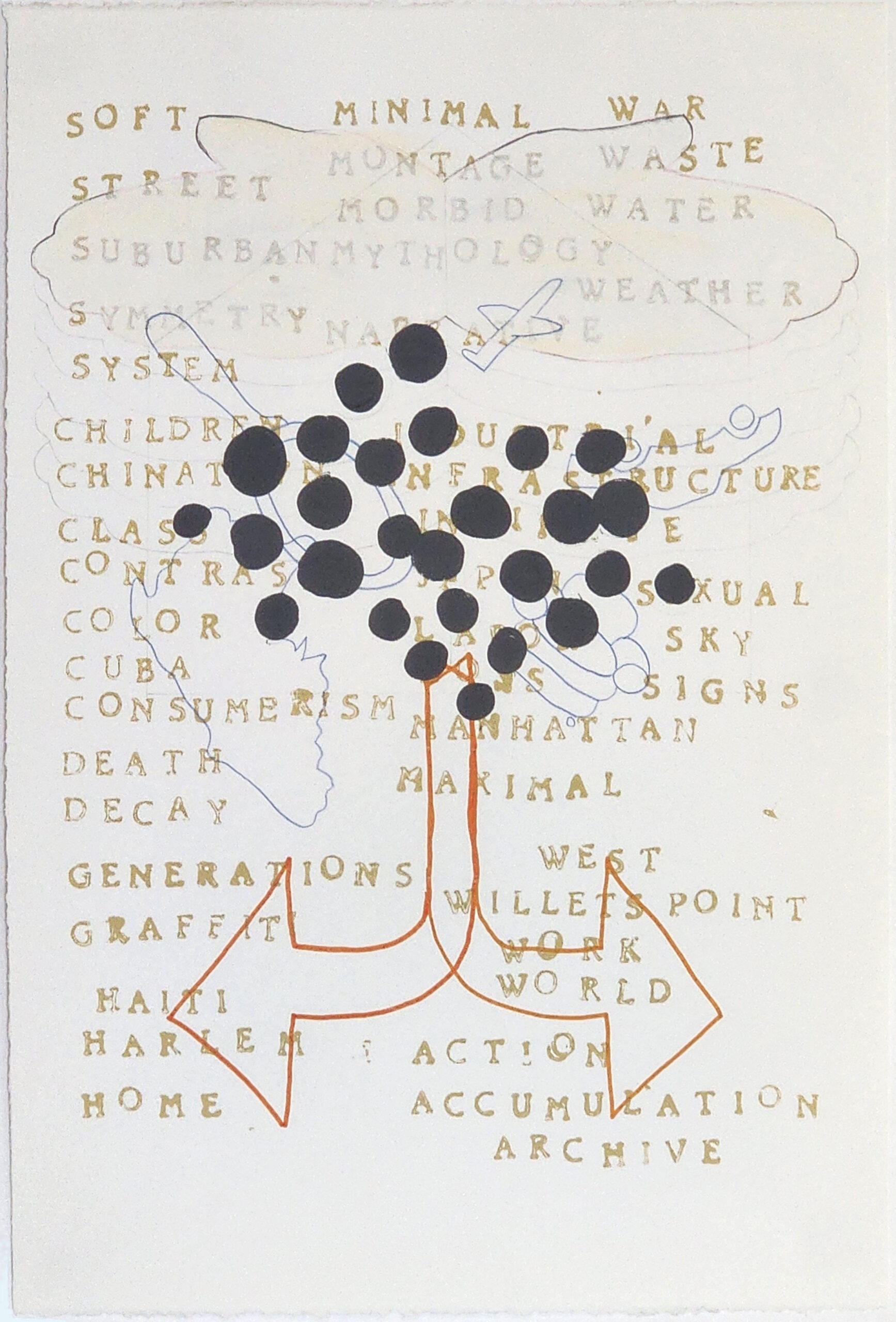

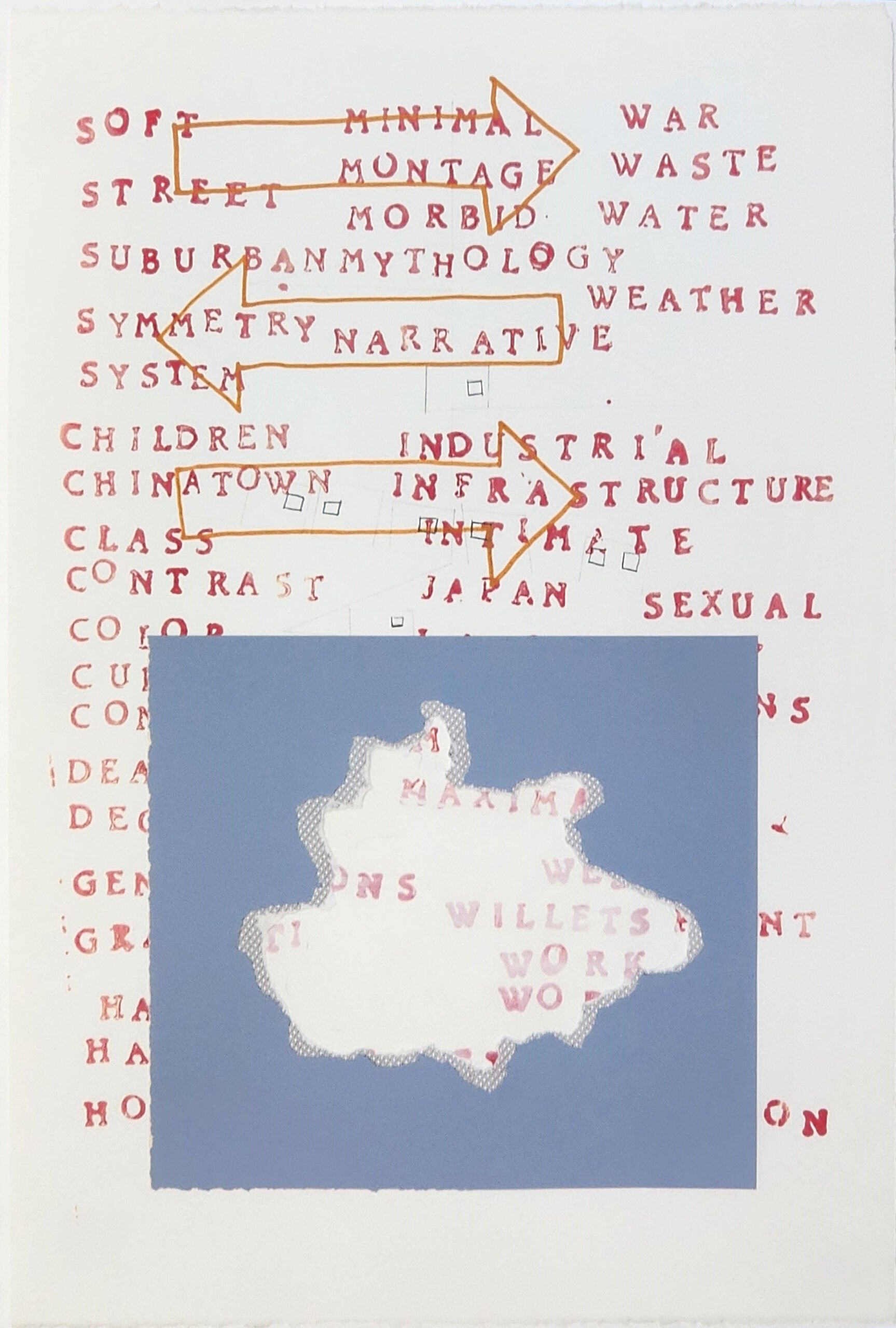

These ideas and meanings led us to a three-part installation: a wall display of low-resolution reference cards of selected reprints of the Nueva Luz digital pages, interpreted through Live, Work, and Inhabit themes; a card catalog of additional reprints and keywords for viewers to handle, to create their own meanings; and original mixed-media drawings inspired by a larger selection of researched images and keywords, imprinting our own perspectives, and offering a renewed reading of the archives.

Rejin Leys (left) is a Haitian-American mixed media artist and papermaker based in New York. She has exhibited in museums and galleries internationally, and her work is included in several public collections. Leys is a recipient of a fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts. She received her BFA from Parsons School of Design (New York, New York) and MFA from Brooklyn College, CUNY (Brooklyn, New York).

Thiago Szmrecsányi (right) is a Brazilian-American visual artist working primarily as a sculptor. He has been a resident artist in the Lower East Side Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural and Education Center (New York, New York) since 1994. He received the Artists Space Independent Project Grant for his curatorial work Insert, produced for the Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space at the Essex Street Market in Manhattan, and a City Artists Corps grant. He participated in The Bronx Museum of the Arts’ Artist in Marketplace (AIM) program and has exhibited in São Paulo, Brazil, and New York. He holds a BA in visual arts from Hunter College, CUNY (New York, New York).

Nueva Luz: Open to Interpretation features projects that demonstrate the importance of En Foco’s archive in stimulating connections between past and present while introducing the creative potential of the rich cultural history found in the magazine’s pages. The multi-part installations on view were developed over eight months of inquiry.

Moving through the gallery from left to right, Shiloah Symone Coley uses images from Nueva Luz to prompt conversations with three lifelong New Yorkers from different generations. Coley identified photographs of daily life in the 1980s by Black women artists Marilyn Nance, Coreen Simpson, Clarissa T. Sligh, and Carrie Mae Weems. Published in the early issues of Nueva Luz, the artists have since become leaders whose insights are widely recognized.

Coley invited three contemporary women to talk about how the photos resonate and why, sharing their own lived experiences during in-person interviews. The recorded conversations are the source for the works here and connect the archive to people’s lived experiences.

The project title You see all that blue stuff? comes from the concept of blue zones—places where people live long, vibrant lives through simple practices, in close connection with each other and their culture. This idea emerges when Kim Hamilton refers to her life and that of her grandmother. In the handwritten quote on the wall, Hamilton ruminates on being surrounded by the arts as she grew up in Queens which reinforces the sense of neighborhood wellbeing with artistic and cultural connections.

The storyboard sequence of four drawings elucidates comments from Yeline Del Carmen, Valerie Nero and Hamilton as they view You Don’t Shine, 1987, silver gelatin print, by Carrie Mae Weems. They each relate to the image of a young girl with boxing gloves as more assertive than defensive.

The power of a photograph from the past to prompt personal recollection is translated to us, the viewer, as an animation. Overall, each part explores a thought, feeling, or experience that connected these women to the work and to each other.

Lisa DuBois was sparked by nine photographs by Adrienne Odom from her series Remaking Harlem documenting Harlem’s architecture from 1997 to 2001. In her artist’s statement, Odom poses the question: “Who will benefit from the remaking of Harlem?” DuBois picks up this query, drawing on her own documentation of the neighborhood where she was born and grew up to create The Fall and Rise of Sugar Hill: An Observation on Gentrification in Harlem. The project’s focus has evolved since mining her own archive and gaining other perspectives by interviewing historian Michael Adams and co-founder of the Dwyer Cultural Center Ademola Olugebefola.

Revisiting Harlem and in particular Sugar Hill with a fresh perspective, DuBois presents a group of her photographs, a video that includes her images with excerpts from interviews with Harlemites who share their perspectives on gentrification. A personal essay recounting her own observations, memories, and experiences informs this work and is included for viewers to read.

The large number of images published in Nueva Luz over a forty year period, combined with the wide-ranging backgrounds of the photographers and their global interests provides a unique data set for investigation and speculation. To create Reimagining Artists’ Spaces, Rejin Leys and Thiago Szmrecsányi selected photos with multiple approaches to portraiture and landscape along with the experimental approach to the medium of photography to evoke a sense of place. They observed the fluidity of workspace for these artists, with many able to work in varied environments worldwide, from fields and forests to war-torn zones

By generating associative words, Leys and Szmrecsányi invented their own index system that is the basis for the categories of Live, Work, and Inhabit. They present the source material as cards displayed in groupings that hint at the relationships they see across time and place. This research matrix inspired a series of mixed media drawings that hint at their process through words and diagrams. Reimagining Artists’ Spaces is a co-created project generated from the pages of Nueva Luz and realized through the artists’ collaborative process.

Jennifer McGregor combines curating and arts planning with ongoing creative projects based on her archive and experiences. Her place-based curating focuses on ecological, historical, and cultural concerns. She works nationally to activate public spaces and create opportunities for artists to engage diverse audiences. She assisted En Foco to launch the Nueva Luz Study Center and the Commissioning Fund. Previously she conceived and implemented arts and cultural programming at Wave Hill in the Bronx.

In 2023, En Foco embarked on a new initiative to commissioning three artists to create new work using the Nueva Luz as a catalyst to explore historical contexts, artists, and themes from a contemporary point of view. Three projects were selected through an open competition. The artists embarked on their investigations last fall and will present their projects at WallWorks (August 1 – 28, 2024) and Volume 28, Issue 2 this fall.

Nueva Luz, one of En Foco’s signature activities, will celebrate its 40th anniversary next year. Since 1985, the magazine has highlighted the work of over 500 photographers, writers and curators. The roster of artists who have been published is impressive. It’s a window to changing concerns, photographic methods and ways of working. For many artists, appearing on its pages has marked a pivotal point, offering artistic validation and a platform to amplify their voices. Each issue includes editorials that connect to the time as well as essays about themes and artists by guest curators and writers.

Nueva Luz Study Center is En Foco’s hub for information about its rich history with digital assets that include:

WALLWORKS NEW YORK is a contemporary art gallery in the South Bronx, dedicated to bringing art back uptown. In the vein of Fashion MODA, WALLWORKS is dedicated to showcasing new and exciting art from both emerging and established artists, mixing “downtown” sensibility with “uptown” style; a place for exploration. The passion project of legendary Graffiti pioneer CRASH and entrepreneur Robert Kantor, WALLWORKS seeks to remind people of the rich culture of the Bronx, and encourage everyone to take a trip Uptown!

Bronx Kreate Hub is a workspace and community incubator in Mott Haven that supports the growth and continued success of local artists, creatives, and entrepreneurs. Community members represent a diverse array of specialties, including animators, graffiti artists, photographers, designers, and community organizations like En Foco and the Mott Haven Film Festival among others. Studio spaces are available at an array of affordable price points, reaffirming Kreate Hub’s commitment to building community through access.

En Foco is supported in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council, National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature, The Mellon Foundation, BronxCare Health System, The Joy of Giving Something, Inc., The Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation, Ford Foundation, Jerome Foundation, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Hispanic Federation, and Aguado-Pavlick Arts Fund.

Header Image Credit: Shiloah Coley, Blue Zone, You See All That Blue Stuff? series, Experimental Animation, 2024. Archival Image courtesy of the Hazel and Jervey Hamilton Family Archive.